Thomas Bewick (1753-1828)

A biographical overview by June Holmes

Childhood

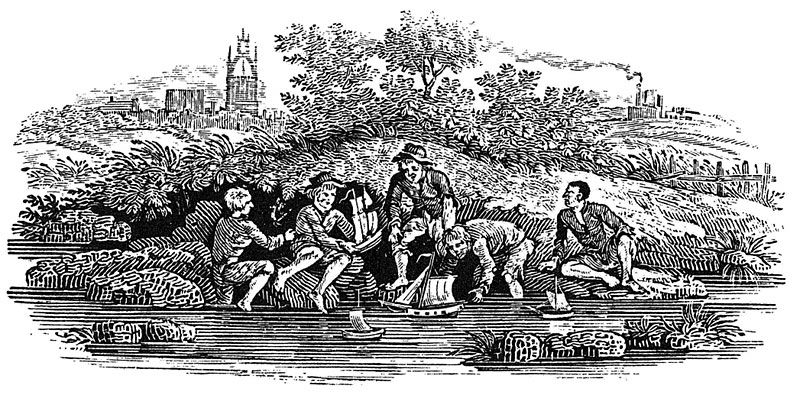

Thomas Bewick, the acclaimed wood engraver, artist and naturalist, was born in August 1753 at Cherryburn House, a small farm on the south banks of the river Tyne, in the parish of Ovingham, Northumberland. His father, John Bewick, who had married his mother Jane Wilson in 1752, was the tenant of a small eight-acre farm and adjacent colliery. Thomas being the eldest of eight children was, as a boy, expected to help around the farm and the colliery. His love of the surrounding countryside often led him to truancy from his tasks and he delighted in roaming about fishing, looking at flowers and watching birds and animals. This proved to have a great influence on his work in later life.

Apprenticeship

He was schooled in the nearby village of Ovingham by the Reverend Christopher Gregson, and at the age of fourteen apprenticed to Ralph Beilby, the owner of an engraving business in Newcastle upon Tyne, twelve miles away. During his seven–year apprenticeship, Bewick was instructed in all the skills necessary to excel in the engraving business, but Beilby was soon to recognise his young protégé’s obvious talent for woodcut engraving. He was set to work on a number of book illustrations, including children’s books such as Tommy Trip’s History of Beasts and Birds, Fables by the late Mr Gay and Select Fables for Thomas Saint, a Newcastle printer.

Partnership

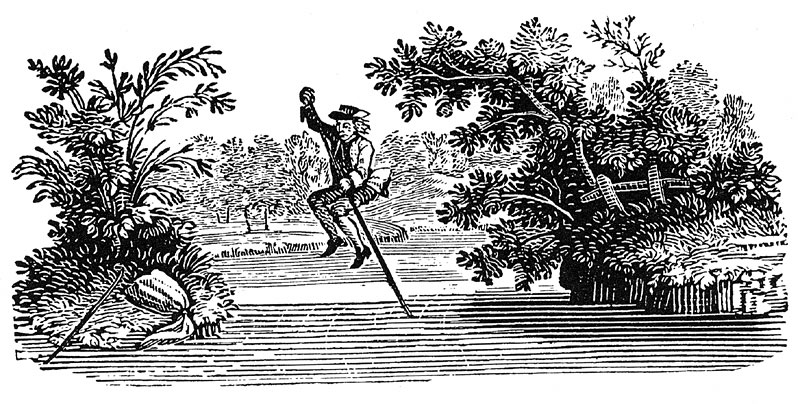

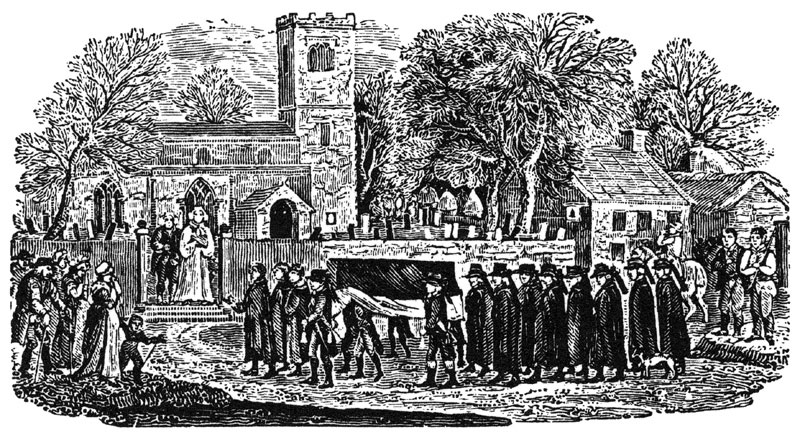

After the completion of his apprenticeship, Bewick decided to enjoy his liberty, which in his Memoir he describes as “a time of great enjoyment”, by setting out alone on foot on a five hundred-mile tour of Scotland. On his return to Newcastle he immediately took a passage on a collier bound for London to try his luck in the “great city”. Bewick disliked London, although he could easily have set up business there, and he returned home to Newcastle as soon as he was able, resuming his association with Ralph Beilby in 1777 as his partner. He took on his younger brother John as his apprentice and they lived together during the whole of this time. (John eventually went to London, and worked there as a successful illustrator until illness drove him home to die in 1795.) After the death of his parents in 1785 Thomas Bewick’s thoughts fixed on marriage and he settled on a local “lass”, Isabella “Bell” Elliot, who “brought him a life of uninterrupted happiness.” They were married in St. John’s Church, Newcastle, in 1786 and had four children: Jane, Robert Elliott, Isabella and Elizabeth (who were themselves destined to remain unmarried).

The engraving business was flourishing and Beilby and Bewick set out on an ambitious project to produce a General History of Quadrupeds. With high motives, this volume, intended to encourage the youth of the day into the study of natural history, was published in 1790 and was exceptionally well received, due in the most part to the freshness and accuracy with which many of the animals were portrayed. With the success of Quadrupeds behind them they turned their attention to a companion work on birds and with this in mind Bewick travelled in July 1791 to Wycliffe Hall near Barnard Castle, the home of the late Marmaduke Tunstall. The partners had come into contact with Tunstall when he had commissioned the large engraving of the Chillingham Bull published in 1789, Bewick’s most celebrated woodcut. Tunstall had formed an extensive private museum collection, which included many stuffed birds, especially foreign species; and with the purpose of researching for the new book, Bewick was invited by William Constable, who had inherited the estate, to spend two months at Wycliffe in order to study the skins. After sketching a large number of the birds, Bewick wrote to Beilby commenting on the enormity of the task and his dissatisfaction with the badly stuffed specimens. They decided to concentrate their book on the British Birds only and two volumes of the History of British Birds were published, Land Birds in 1797 and Water Birds in 1804. It is here we see Bewick at his best as a keen observer of wildlife, drawing in most part from his own experience or from fresh specimens sent to him by his many friends and admirers.

Independence and fame

The partnership of Beilby and Bewick ended acrimoniously in January 1798 and Bewick, retaining the engraving business, went on to publish further revised editions of Quadrupeds and British Birds. The business included a full range of engraving work of other kinds, such as engraving on glass and on silver, as well as copper engraving. There was a large volume of commercial jobbing work of these kinds in addition to commissions for wood-engraved illustration, such as for The Poetical Works of Robert Burns, printed and published in Alnwick by William Davison in 1808; the title page shows the phrase “ornamented with engravings on wood by Mr Bewick, from original designs by Mr Thurston.” He turned his attention in 1812 to a new, but long-cherished wood-engraving venture, The Fables of Aesop and Others, eventually published in 1818. Fables and moral tales had formed a greater part of his boyhood reading and the interest had continued into his adult life, inspiring many of his vignettes or “tale-pieces” as he called them. Thomas Bewick died in 1828 at the age of seventy-five, leaving the engraving business to his son Robert and a wealth of watercolour and pencil drawings, woodblocks and engravings assiduously collected, over many years, by his family. Robert continued to publish two further editions of the Birds in 1832 and 1847 (the latter edited by John Hancock, the ornithologist and taxidermist) and also Bewick’s last work, a large engraving on wood, Waiting for Death, published posthumously in 1832.

Pressed by his daughter Jane to produce an account of his life, Bewick had completed a manuscript of his Memoir which he commenced in 1822, but it was destined to lie fallow for many years, eventually being published, in a much edited state by Jane in 1862.( It has been re-published in the 1970s, edited by Iain Bain in a version following the original manuscript exactly, including Bewick’s occasionally erratic spelling.) Bewick Memorial at the site of his Newcastle workshop

Afterlife

A celebrity in his own life time, the great fascination with Thomas Bewick’s life and work continued unabated throughout the lives of his family and carried on long after their deaths. When Isabella, the last surviving member of Bewick’s four children, died in 1883 the family possessions were dispersed. A large collection of watercolour and pencil drawings were presented to the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne; this included all the family portraits of Bewick. Isabella Bewick had previously deposited another large collection of drawings at the British Museum in 1882. Some of the personal belongings went to the Ward family, relatives of Thomas Bewick’s great nephew Robert Ward and the rest was auctioned. The interest carried on with numerous avid collectors of Bewick memorabilia, such as the Reverend Thomas Hugo, Edwin Pearson, Robert Robinson and John William Pease, to name but a few, bringing together formidable assemblages of Bewick’s work, some of which are preserved in the Pease Collection, Central Library, Newcastle.

A celebrity in his own life time, the great fascination with Thomas Bewick’s life and work continued unabated throughout the lives of his family and carried on long after their deaths. When Isabella, the last surviving member of Bewick’s four children, died in 1883 the family possessions were dispersed. A large collection of watercolour and pencil drawings were presented to the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne; this included all the family portraits of Bewick. Isabella Bewick had previously deposited another large collection of drawings at the British Museum in 1882. Some of the personal belongings went to the Ward family, relatives of Thomas Bewick’s great nephew Robert Ward and the rest was auctioned. The interest carried on with numerous avid collectors of Bewick memorabilia, such as the Reverend Thomas Hugo, Edwin Pearson, Robert Robinson and John William Pease, to name but a few, bringing together formidable assemblages of Bewick’s work, some of which are preserved in the Pease Collection, Central Library, Newcastle.

Many biographies and articles have been written about Thomas Bewick, including books lavishly illustrated with drawings and engravings. Authoritative authors, such as Iain Bain and Nigel Tattersfield, have taken the study of Bewick’s life and work to greater heights with their extensive research in these and other archives. It was the sale of the Cherryburn estate, the birthplace of Thomas Bewick, in 1982, which sparked a resurgence of interest in Bewick in the North East. The Thomas Bewick Birthplace Trust was formed by a group of enthusiasts with the aim of raising funds to purchase and restore Cherryburn and provide a small museum for visitors at the birthplace cottage and at the larger farmhouse, which had built in the 1820s by his brother’s family. Officially opened in 1988, to great acclaim, the museum was run by the Birthplace Trust and eventually handed over to the National Trust in 1991. Within the auspices of the Bewick Birthplace Trust, The Bewick Society was officially launched on May 22nd 1989 by Bamber Gascoigne, TV presenter and print enthusiast, with the aim of promoting a greater interest in Bewick’s legacy world wide.